Huffington Post: Orangutan Rescue in Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem

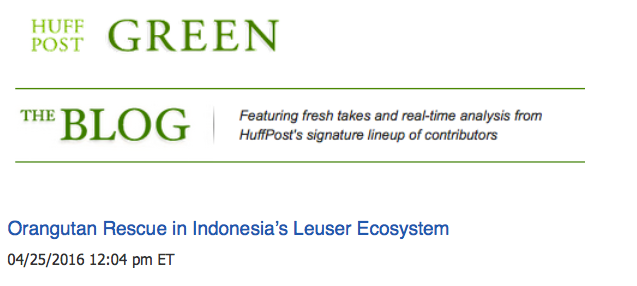

Medical check of orangutan. Photo courtesty of Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Program (SOCP)

The adolescent orangutan was on his way to becoming the illegal pet of a police lieutenant in Jakarta in 2004 when a team from the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Program (SOCP) and the Ministry of Forestry’s Conservation Department in Aceh (BKSDA Aceh) intervened and confiscated the five-year-old male ape. They called him Leuser, in honor of where he came from — the Leuser Ecosystem.

The Leuser Ecosystem

Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem, on the northern end of the island of Sumatra, is a 10,000 square mile (2.6 million hectare) biodiversity hotspot that encompasses a variety of terrain from mountains and tropical rainforest to lowland forest and peat swamps. It is often referred to as “the last place on earth” because it is the only remaining habitat shared by critically endangered Sumatran elephants, rhinoceros, tigers and orangutans.

Even so, palm oil barons, illegal loggers and mining companies want to develop it. That further threatens Sumatran orangutans, whose populations are declining rapidly due to habitat loss. A recent study estimated the population at roughly 14,600 in 2015, and warned that numbers will likely plummet by 14 to 33 percent over the next 15 years.

Land Clearing and Its Victims

Clearing the land for oil palm plantations hurts orangutans, who not only lose their homes and food but come into increasing contact — and conflict — with farmers and villagers.

When a palm oil company goes in, it fells the timber and then sets fire to whatever remains to make way for oil palm seedlings — planted in long marching rows. This slash and burn technique is seen as a quick way to clear land for new plantations —yet it creates many interconnected problems.

A lot of the cleared land is peat forest that burns like a roaring barbecue. And even when fires above ground die, fires underground can continue for months and spread to new, unintended, places. The fires not only destroy massive amounts of former forest, but also release huge amounts of greenhouse gases. In late 2015 alone, Indonesia’s record fires — triggered by a combination of bad land use management and one of the strongest El Nino’s in history — burned through tens of thousands of hectares, which resulted in haze, respiratory infections in up to 500,000 people and emissions of 1.4 billion tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases, more than Japan’s annual release.

Orangutan rehabilitation

While it’s illegal to capture, kill, or keep an orangutan as a pet in Indonesia, prosecution is rare and orangutans often meet these fates.

Leuser, the adolescent orangutan, was one of the “lucky” ones confiscated by authorities and brought to a rescue facility.

Leuser was first brought to SOCP’s quarantine center near Medan, where all new arrivals spend 30 days in quarantine for medical exams, treatment and to ensure they carry no illnesses that could infect others.

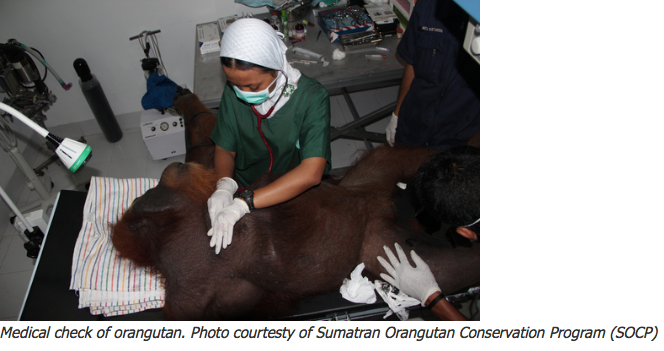

Leuser the blind orangutan. Photo courtesy of Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme.

Once rescued orangutans are healthy again, they are typically transferred to one of two locations, Jambi or Jantho, for release back to the wild. By design, both locations are outside the Leuser Ecosystem, which is home to roughly 85 percent of the world’s remaining wild Sumatran orangutans. That concentration is of concern to scientists, because a single disease outbreak could wipe out the entire population. That’s why SOCP releases its rescued orangutans at Jambi and Jantho, which is not only prime habitat but it has the additional benefit of acting as an “insurance policy” by building two populations separate from the Leuser Ecosystem.

SOCP hopes to release around 25 to 30 orangutans each year until there are at least 350 at each location. That’s the number, SOCP director Ian Singleton says, that can ensure a viable and sustainable community of more than 250 surviving, thriving and even more importantly, breeding orangutans.

Leuser’s Release

After his quarantine, Leuser was transferred to Jambi in June 2004 but in November 2006, SOCP received a call saying that villagers had captured an orangutan on a plantation, 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) from the park boundary. A team moved in and quickly recognized the orangutan. It was Leuser.

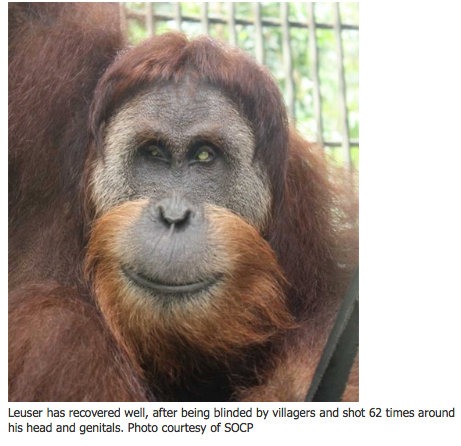

He was in bad shape. He had a 40 centimeter (nearly 16 inch) cut down his right leg and his body was riddled with air rifle pellets — 62 of them concentrated around his head and genitals. Both his eyes had been shot.

The team took Leuser back to the quarantine center. Veterinarians could only safely remove 14 of the 62 pellets. He was left totally blind.

Xray of pellets in Leuser the orangutan’s skull. Photo courtesy of Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme.

Three villagers were prosecuted for shooting Leuser and received 6-month jail terms. They claimed they wanted to capture the animal and sell it to an orangutan project, yet evidence suggested they shot Leuser just for fun.

While he’s made a full recovery except for his blindness, he must remain at the SOCP’s center because he can’t ever return to the wild. However, Leuser’s story is still unfolding. With the recent release of his son into the forest, his progeny will be a key link for the survival of his species.

To learn more about Leuser, his mate Gober and their offspring, read the full story in Mongabay.com‘s Great Ape series, titled Leuser’s Legacy: how rescued orangutans help assure species survival. This article is an excerpt and published with permission.