Mongabay.com: Pet trade, palm oil, and poaching: the challenges of saving the ‘forgotten bear’

By Laurel Neme, special to mongabay.com

March 20, 2011

This interview originally aired May 17, 2010. It was transcribed by Diane Hannigan.

Siew Te Wong is one of the few scientists who study sun bears (Ursus malayanus). He spoke with Laurel Neme on her "The WildLife" radio show and podcast about the interesting biological characteristics of this rare Southeast Asian bear, threats to the species and what is being done to help them.

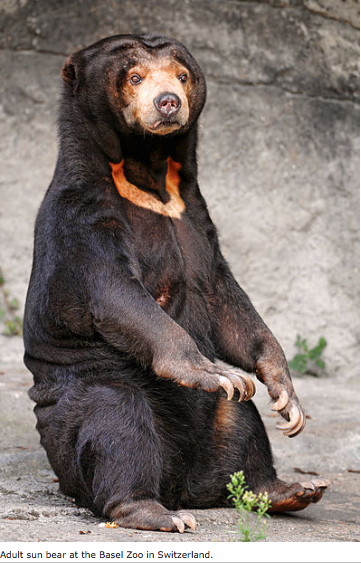

Sun bears are the smallest of the eight bear species. They’re about half the size of a North American black bear and typically sport a tan crescent on their chests. Similar to the "moon bear," or Asian black bear, the sun bear’s name comes from this marking, which looks like a rising or setting sun.

Sun bears live in Southeast Asia and are probably the least known bear species in the world. They have been so long neglected that Wong refers to them as "the forgotten bear species." One of the reasons may be that they are difficult to study because they’re nocturnal and spend most of their time up in the trees.

Nobody knows how many sun bears remain in the wild. However, they are under significant threat and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists them under Appendix I. Habitat loss is the primary concern but these diminutive bears are also threatened by the pet trade and poaching for their parts, which are used in traditional Asian medicine.

For the last 14 years, Wong has dedicated his life the study and ecological conservation of the sun bear. Wong's research has taken him to the most threatened wildlife habitat on Earth, where fieldwork is exceedingly difficult.

His pioneering studies of sun bear ecology in the Borneo rainforest revealed the elusive life history of the sun bear in the dense jungle.

While rapid habitat destruction from unsustainable logging practices, the conversion of the sun bear's habitat into palm oil plantations and uncontrolled poaching activities paint a bleak picture for the future of the sun bear, Wong is helping sun bears both through his research and through the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, which he founded in 2008.

Wong is one of a handful of Malaysian wildlife biologists who has trained in a western country. He did both his Bachelor of Science and Master of Science degrees at the University of Montana in Missoula, and is finishing his doctorate there. He is former co-chair of the Sun Bear Expert Team, under the IUCN/Species Survival Commission’s Bear Specialist Group, and a current member of three IUCN/SSC Specialist Groups. His dedication was recognized when he was named a fellow of the Flying Elephants Foundation, which awards individuals from a broad range of disciplines in the arts and sciences who have demonstrated singular creativity, passion, integrity and leadership and whose work inspires a reverence for the natural world.

The following is an excerpt from The WildLife with Laurel Neme, a program that probes the mysteries of the animal world through interviews with scientists and other wildlife investigators. The WildLife airs every Monday from 1-2 pm Eastern Standard Time on WOMM-LP, 105.9 FM in Burlington, Vermont. You can livestream it at www.theradiator.org or download the podcast from iTunes, www.laurelneme.com, or http://laurelneme.podbean.com. This interview originally aired May 17, 2010. It was transcribed by Diane Hannigan.

INTERVIEW WITH SIEW TE WONG

Laurel Neme: What’s special about sun bears?

Siew Te Wong: They’re very unique to me! When you ask that question to biologists they’ll tell you the species they’re studying is always special, always unique, because they love them so much. So, it will be the same for me!

Laurel Neme: Where do they live? Are they unusual because they are an arboreal bear?

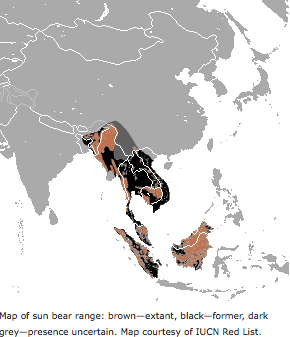

Siew Te Wong: Sun bears are found in Southeast Asia in ten different countries… ranging from the eastern tip of India to the southern tip of China in Yunnan province, across Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, islands of Sumatra, and the island of Borneo. It’s a tropical bear. They’re the smallest of all the bears [family Ursidae], and weigh [about] a hundred pounds.

SUN BEAR RESEARCH

Laurel Neme: How many people study sun bears?

Siew Te Wong: At the time I started my study back in 1998, there were three people, including myself, studying sun bears in Borneo. I was working on my Masters degree and the other two were working on their PhDs. Last year there were three or four additional projects—two in Sumatra, and one in Thailand, and one on the peninsula of Malaysia. So, after all these years, less than 10 people in the world have ever studied sun bears. Period. Compared to other large mammal species, the numbers are so low. We are so behind in generating scientific information on sun bears.

Laurel Neme: Do all of you exchange information? What’s a party like between all of you? [Laughs].

Siew Te Wong: I’m working really hard trying to get everyone to collaborate and exchange information as much as possible. Since I’m one of the first people to do this work, I want to assist as many students and biologists as possible to do their work. I have spent a lot of time in the forest to learn about sun bears the hard way. If I can pass my knowledge on to others, they don’t have to learn the hard way. I’d love to do that. Almost everyone is in close contact with me. I try to give my advice and my opinion as much as possible—even help them do their studies.

Laurel Neme: Given that they are so difficult to find in the forest, how do you go about studying them?

Siew Te Wong: The first challenge is to catch them and put a radio collar on them. To study large mammals like sun bears [the first thing to do is] put a radio collar on them to follow them in the forest. [Then] we try to get close to them and see what they do. We collect their [fecal matter]. [From that] we can know how large their range is and so on.

[Early on] we tried to catch them without any sort of experience. Back in 1999, I had some help from some bear biologists from here, [and] they helped me set up traps out of wood and metal.

Laurel Neme: What did the traps look like?

Siew Te Wong: At the time, we used three kinds of traps. The first kind of trap was a wooden box trap, made out of 3’x3’ lumber. It’s similar to the trap used in North America to trap wolverines. [Then] there’s the aluminum culvert trap that we custom-made in Montana. The beauty of this trap is that it can be taken apart into nine pieces and then we can backpack the whole trap into the forest and then put it back together. The third kind [of trap] is the 55-gallon barrel trap.

Laurel Neme: How did you bait them?

Siew Te Wong: At the time, no one had trapped sun bears before, so I tried all different kinds of bait including all the fruits and honey. After months of trial and error, I figured it out. The best bait to catch sun bears is chicken guts. It’s cheap, it’s smelly, and the bears love it. [Laughs]

SUN BEAR DIETS

Laurel Neme: Sun bears are not strictly herbivorous?

Siew Te Wong: Sun bears are bears. They’re carnivores in design, but they end up eating whatever they can find. Fruits, of course, are one of the items they can find in the forest. If they could find carcasses or hunt prey, I’m sure they would.

Laurel Neme: Was that known before you started studying what they eat?

Siew Te Wong: Yes and no. From captive animals we knew they are omnivores and eat almost everything. The zookeepers give them meat. Other species do the same thing. The sloth bear, or the spectacled bear, or the Indian bear, we know they eat a lot of plant material but they’ll also eat meat [if they have access to it].

Laurel Neme: Will sun bears kill prey or are they simply opportunistic, in that if they’ll find a carcass they’ll consume it]?

Siew Te Wong: They’re more opportunistic. In the forest, if there are some prey items that are easier to catch, then they’ll definitely go for it. For example, they prey quite a bit on tortoises.

Laurel Neme: They can get at the tortoises with the shell?

Siew Te Wong: Apparently they can use their long claws. The shell is not closed up completely. There are some soft spots where the bears can easily use their claws and canines to damage and kill it.

Laurel Neme: What else do the bears eat? You mentioned earlier that they eat insects.

Siew Te Wong: In 1999-2000, during my first ecological study of sun bears, the forest did not have any fruit in season. The bears were feeding on invertebrates like termites, beetles, beetle larvae, earthworms and any insects they could get.

[Beetle] larvae can grow to as much as three to four inches long. They’re packed with fat and protein. A sun bear can spend an hour or two digging at a decayed [piece of] wood trying to fish out beetle larvae. The moment they fish one out, you can tell from their facial expression—[it’s like] they’re having the best chocolate in their life!

Laurel Neme: What does this happy expression look like?

Siew Te Wong: First of all, they close their eyes! I’m not sure if you can notice or not, but bears smile like humans or dogs. When they smile, they pull their facial muscles backwards, so it looks like their smiling. They’re just like humans when tasting a nice piece of chocolate. You close your eyes and let the chocolate melt in your mouth. It’s exactly the same expression when they have big, fat, juicy, packed-with-protein beetle larvae in their mouth.

Laurel Neme: Have you tried the beetle larvae?

Siew Te Wong: No! I’m not that desperate!

Laurel Neme: [Laughs] They still eat the larvae even when fruit is available in the forest?

Siew Te Wong: Yes! And the forests of Borneo have a unique feature where they don’t fruit annually. The forest goes through something called mass fruiting. The mass fruiting occurs every two to eleven years. During the non-fruiting years, the bears feed on invertebrates. Also, there are a few species of plants that do not follow the mass fruiting, like fig and ficus.

Laurel Neme: Is there a lot of competition for the fig and ficus?

Siew Te Wong: There’s a lot of competition between the bears in a period when there is no fruit around. From my study, from the bears that I captured, they all have different kinds of scars and wounds from fighting. They have a tough life. They compete with each other because food resources are so low.

But for the ficus, it’s something different. They’re big and can produce big crops. There’s no need to compete for this kind of fruit. The resources are available [to the bears] for a period of two weeks or so. One strangling fig [a kind of ficus] can put out about 2 million fruits at a time, so there’s no need for competition. I have evidence of three different bears feeding on the same tree at the same time. I’ve also witnessed one of my radio collar bears feeding on top of a fig tree, and then on the same tree there was a female orangutan with babies, a binturong (Asian bearcat) with babies, gibbons, and all kinds of birds and squirrels. It’s a very spectacular sight.

Laurel Neme: Is the fruiting seasonal or by year?

Siew Te Wong: The fig tree is not seasonal. They fruit individually throughout the year. Some species fruit twice a year, some put out three different crops a year. The reason they do it [that way] is to maintain a healthy population of fig wasps, their only pollinators.

ROLE OF SUN BEARS IN ECOSYSTEM

Laurel Neme: What’s the role of sun bears in the ecosystem?

Siew Te Wong: They do two big things for the forest. One, they are frugivores. They’re large mammals, so they eat big fruit with big seeds, for example, durian—the king of fruits in Southeast Asia. When they eat the fruit they disperse the seeds. Sun bears are important for seed dispersal in the forest ecosystem. They pretty much plant the forest. The seeds need to be carried far away from the mother tree to enhance the germination period and the survival rate of the trees.

[Second], by feeding on invertebrates like termites, they break the termite mound and they break apart decaying wood. They are actually creating another type of niche, another type of feeding site for other animals. They don’t finish everything, which leaves another site for other animals to feed on.

They’re considered an ecosystem engineer. [Another example is that] they feed on beehives. The beehives are in tree cavities, so they have to break into the main trunk of the tree in order to get to the beehives and they create cavities. These will later be used by [other animals like flying squirrels] to make nests. [Since they] prey on a lot of termites, they actually maintain healthy forests because termites have the reputation of killing or infesting trees. By reducing the number of insects that are harming plants, they do the plant community a good thing by keeping these pests at a healthy level.

ESTIMATING SUN BEAR POPULATIONS

Laurel Neme: What is the conservation status of sun bears? Are they endangered?

Siew Te Wong: Yes, they are an endangered species. They are listed under the IUCN Red List as a Vulnerable species. They just got this status in 2008. Before that, they were listed as data deficient because so few people had studied them. We didn’t have the scientific information to know how many sun bears there are in the world. Now, we have estimates.

Looking at the big picture, looking at the deforestation rates in Southeast Asia and with the forest disappearing so fast, we know the sun bears are in big trouble. We know their population has declined by more than 30 percent over the last 30 years. With all the poaching, hunting, and pet trade going on in the region, [we know] sun bears are in trouble. Although I do not have the numbers of how many sun bears there are, from my experience working in the forests of Borneo, I know the numbers are lower than orangutans, for sure.

Laurel Neme: What would it take to do a population census? Is it possible?

Siew Te Wong: Yes and no. I tried to estimate the number of bears in the forest and I pretty much failed because I haven’t come up with a reliable method to do it. Right now the method that people use most is called catch and recapture. By assessing the capture rate and recapture rate, we can estimate how many there are in the wild.

This method has been widely used by tiger biologists. [But they can use it because] individual tigers are recognized by cameras. This method is not applicable to sun bears because individuals cannot be identified from a camera picture because they’re just black; they don’t have a special marking.

Laurel Neme: What’s an alternative method that researchers commonly use for population studies?

Siew Te Wong: Another method is to use DNA. So far, a bear’s DNA is quite difficult to collect because in a tropical forest it rains every day and the genetic material is very difficult to obtain.

THREATS TO SUN BEARS

Laurel Neme: What are some of the biggest threats to sun bears? You talked about habitat destruction, poaching, hunting, and pet trade. Which is most important?

Siew Te Wong: What you mentioned are all threats but, by far, habitat destruction is the biggest threat for sun bears in Southeast Asia.

Laurel Neme: Why is that?

Siew Te Wong: Sun bears are a forest-dependent species; they have to live in a forest. When you see a landscape being cleared, a forest being cut down and replaced with plantations, replaced with development, sun bears have lost their home forever. The deforestation rate in Southeast Asia is horrible, with plantations replacing the tropical rainforest. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to see how seriously sun bears are affected by deforestation.

The second threat, which I mentioned earlier, is the poaching for bear parts. This is still ongoing. They’re poached for their gallbladder, their claws, their canines, their meat, and many [other] purposes, especially for traditional Asian medicine.

Laurel Neme: Then there is the pet trade.

Siew Te Wong: Sun bears are really cute. They’re the smallest of the bears. Because they are small and cute, people love to keep them as pets. [At the same time] deforestation [provides greater access to the interior of the forest] and baby bears are more vulnerable. People poach the mother, capture the baby, and then the baby becomes a commodity in pet trade.

Laurel Neme: Do they make good pets, or do they grow up?

Siew Te Wong: They absolutely do not made good pets! They’re big animals with big claws and strong canines; they’re very destructive. No one can tame a bear. In the end, they’re locked up in metal cages, which is very sad. The situation is quite desperate.

BORNEAN SUN BEAR CONSERVATION CENTRE

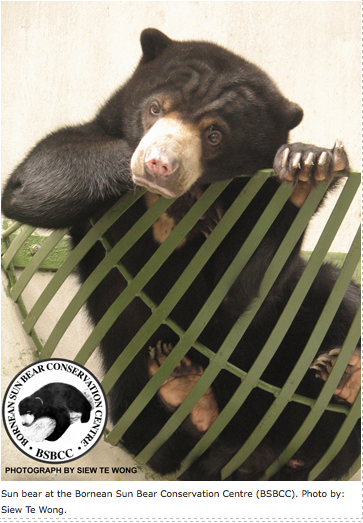

Laurel Neme: You helped found the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre (BSBCC) in Sabah, Malaysia in 2008. How did the Center come to be? Is that the reason behind founding it?

Siew Te Wong: At first, back in 1998, it was just a project. I noticed there were a lot of sun bears being held in captivity. Private owners kept them as pets, or [they were] on crocodile farms or zoos. [All these places] had a lot of sun bears, and they were all very sad. They roam the forest but [at these places] they were locked up in small cages. They shook their heads all day long with stereotypical behaviors [of animals in captivity]. No one tried to do anything about it. Sun bears are a protected species in all of the countries where they are found. No one is allowed to hunt sun bears by law or keep them as pets. But, because of the lack of law enforcement and lack of interest to conserve the species, these kind of things happen.

[If you keep one as a pet], you need to obtain a special permit. Southeast Asia is a developing country; wildlife crimes are of little priority compared to crimes against humans, so a lot of the laws are not enforced. People keep bears because they’ll never get caught.

Given the lack of interest among other NGOs, I decided "[if] you guys aren’t going to do [something,] I’m going to do it." The first group of animals that I wanted to help was the caged animals. [I think] people had to be told, "No, you can’t keep sun bears as pets. It’s against the law!" [So, when] I founded the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre, the first thing we wanted to do was rescue the caged bears.

The second thing was to educate the people. We needed to show them how special and unique sun bears are and what important role they play in forest ecosystems. We wanted to do conservation work, rehabilitate those sun bears back into the forest, and continue to do research.

Laurel Neme: How did you get funding for it?

Siew Te Wong: Funding is very challenging. This project I didn’t do myself; it wasn’t possible to do all by myself. I was very fortunate to have help from a local NGO from Sabah called LEAP. It stands for Land Empowerment Animals People. They helped me establish [the project] and we created a partnership between the Sabah Wildlife Department and the Sabah Forestry Department. These were the two agencies that helped establish the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre.

Laurel Neme: It’s unusual to have government agencies so involved in something like this.

Siew Te Wong: Yes. There’s usually lack of interest to set up [conservation] centers by the government. As biologists, as conservationists, we work together to assist the governments to set up the Center. The resources came from private entities and they collaborated with the government. The bears actually "belong" to the government, to the country, so we need to have the Sabah Wildlife Department be involved in the project in order to make it successful. [Plus,] the land that we release the bears into actually belongs to the Forestry Department. It makes sense that [these two departments] are partners on this project.

The funding for this project was not cheap. We needed about $1 million to set it up. Because we had no money to start with we had to raise this money. We divided the project into three different phases. Phase one needed about $400,000. In November 2008, we held a fundraising dinner where we raised close to $300,000 in one evening. That evening the government declared a matching fund. So, this project is half funded by the Sabah government.

The first phase of the project was finished in March 2010 and involved construction of a bear house that can house 20 bears and also a 1-hectare forest enclosure. Now, we’re officially in stage two. This includes refurbishment and upgrading of the old bear house and also renovation of the offices. We’ll have a visitor gallery, boardwalks, and an observation boardwalk for people coming to visit. [Phase III consists of the construction of the second block of bear houses and forested enclosures for 20 additional bears.]

One of the unique things about our project is our location. Our enclosure is next to a well-known orangutan rehabilitation center [Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre (SOURC)], where hundreds of tourists come. We want to open our facility as well because we want to educate those people about sun bears and let them see sun bears in their natural environment. We also want to generate revenue from tickets to run our conservation and education program. We are side-by-side. The (orangutan) rehabilitation center is run by the Sabah Wildlife Department and my project with sun bears is also a Sabah Wildlife Department Project. So, we share the same facilities. [Due to their close proximity, the BSBCC utilizes existing SOURC veterinary facilities and personnel, parking, access roads and ticket gates. It also links to existing forest trails and boardwalks at SOURC.]

Laurel Neme: How many bears do you currently have?

Siew Te Wong: The bears at our Center were confiscated by the Sabah Wildlife Department. We have twelve bears right now (May 2010). After our bear house is built, we’ll have another four bears come in about two weeks from now. After that, we have an additional ten other bears lined up to come in. We’ll be at capacity about one month after we finish our first bear house.

This will lead us to phase three in which we build another bear house and another forest enclosure. As you can see, there are a lot of bears in captivity that need to be rescued and taken care of.

SUN BEAR REHABILITATION AND RELEASE

Laurel Neme: Do you have an idea of how many bears need to be rescued?

Siew Te Wong: In Sabah, there are at least 50 bears that need to be rescued. I’m sure there will be more in the future. [In other places in Southeast Asia] there are hundreds to thousands. Different locations have their own problems.

Laurel Neme: Are there plans to release them into the wild and what would it take to release them?

Siew Te Wong: It takes a lot of time, resources and manpower to release them. But I think it is the right thing to do and I believe they are [able to be rehabilitated]. It is not easy. It is very time consuming. What we plan to do is select the bears that still have strong instinct and walk them in the forest every day. This is a slow process. We don’t bring the bear into the forest, open a cage, and say "good luck." We live with the bears in the forest for years until they are strong enough to fend for themselves, until they are knowledgeable enough to know where food is, and until they have established their home range.

Laurel Neme: Have you already begun to identify bears for release?

Siew Te Wong: Well, we just started. We just moved bears to the bear house and forest enclosure, so we’re just starting to study the individual animals to see who can be the first potential candidates to be released into the wild.

TALES OF RESCUED BEARS

Laurel Neme: Tell me about some of the bears you have rescued.

Siew Te Wong: One is a bear cub is named Chura. Chura is with us right now. Chura is a good candidate [for rehabilitation and release]. [We have a couple other females] that we’re trying to establish a relationship with the keepers. The bears will trust our keepers and then we’ll eventually be able to walk the bear in the forest hopefully in the next year or so. You can see on my YouTube channel about big males that may or may not be good candidates. We’ll have to observe how they perform in the forest enclosure first. [Note: Beartrek, a big screen movie produced by Wild Life Media about bear research will feature Siew Te Wong trying to reintroduce baby bears into the wild. The promo, available on YouTube, shows Chura.] Laurel Neme: What makes Chura a good candidate?

Siew Te Wong: Instinct is very crucial. It’s actually pretty sad. For sun bears kept in captivity, they have been kept in small cages or have walked on cement floors for years. They have been fed with human food. [They reach] a point where they lose their instincts. They can’t recognize, for example, termites as their natural food. We have to identify those that still have their instincts. We’ll give them the opportunity to eat termites and present them with decaying wood. They’ll pick it up right away, sniff it, and break it apart, and see what they can get out of the termite nest, or they’ll just leave it alone. The bears that have lost their instincts do not associate that kind of thing as their natural food. These would be bad candidates to release.

Bears are just like humans in that they have different personalities. Some are smarter than others, more alert than others, or more cautious than others. We want to pick out the bears that are alert, smart, and have a strong instinct to forage in the wild. These are the components to their success.

HOW TO HELP SUN BEARS

Laurel Neme: What can people do to help if they get interested in sun bears? Where can they go for more information?

Siew Te Wong: People ask, "How can I help?" I always answer,"whatever you do best!" Artists, help us paint paintings of sun bears and sell it at auctions to raise funds. Reporters report about our work. And, of course, everyone is on Facebook. Join our sun bear conservation Facebook cause. Get in touch with us. Anyone can help.

Understand that sun bears are the least known bears in the world. There are so many people that have heard about polar bears, grizzly bears and giant pandas, but they’ve never heard about sun bears. By helping to spread the word about sun bears, showing people pictures of them, by putting stories about sun bears on Facebook, they help us to promote awareness. Unfortunately, our conservation work spends money. Generally, the amount of money we raise reflects the amount of work we can do to help a species. [But] fundraising for an animal that is not well known is not easy.