National Geographic: Inside the Secret Trade That Threatens Rare Birds

Singapore is a major transit hub for trade in threatened birds, especially African grey parrots.

Singapore plays a key role as a major international transshipment hub for the global aviculture industry, according to a new study by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the wildlife trade monitoring organization TRAFFIC. That’s especially true for trade in African grey parrots.

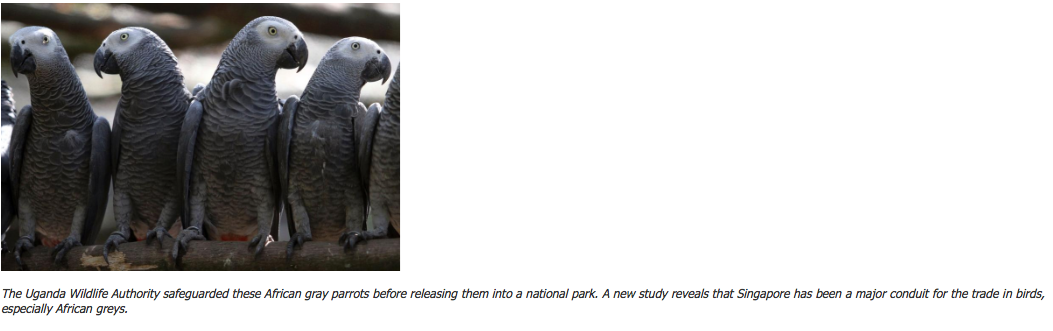

African greys are highly sought-after as pets because they’re so smart and talkative. (Alex, who lived with scientist Irene Pepperberg for 30 years, had a vocabulary of more than a hundred words and a mind-blowing range of cognitive skills beyond.) They’re native to Equatorial Africa, but populations are declining throughout their range. Although millions of African greys have been bred in captivity, demand for wild-caught birds remains high, and they’re especially vulnerable because they roost in large groups and tend to concentrate around water sources or mineral licks.

They’re now so popular that some range countries have proposed that the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the body that regulates the global wildlife trade, categorize them as requiring maximum protection.

The new study, published in the journal Oryx, sheds light on the bird trade system. It reveals that Singapore has been a major conduit for birds from Africa and Europe to East Asia and the Middle East and that between 2005 and 2014 the city-state imported 212 bird species listed by CITES as needing protections, with African grey parrots the most intensively traded.

The study also uncovered discrepancies in the trade data. While Singapore imported nearly 225,600 birds during that period, just 60 percent were reexported, leaving as many as 86,000 birds unaccounted for.

From his Malaysia office, Chris Shepherd, TRAFFIC’s Southeast Asia regional director and the co-author of the study with WCS’s Colin Poole, explains how these inconsistencies in the trade records are an opportunity for Singapore to employ best practices in the international wildlife trade.

Why did you undertake this study?

Singapore plays a very significant role in the international bird trade. Between 2005 and 2014, a total of 212 CITES-listed bird species have been imported to Singapore, with 29 of them assessed as vulnerable, endangered, and critically endangered by the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] Red List of Threatened Species. The vast majority of the CITES-listed birds traded in or through Singapore are parrots and cockatoos.

This study also showed that Singapore imported CITES-listed birds from 35 countries and exported to 37 during the study period. That means Singapore is well positioned to be a regional or global leader by employing best practices in the regulation, compliance, and monitoring of the international trade in wildlife.

Past studies undertaken by TRAFFIC highlighted not only the significant volume of birds traded in and through Singapore but also that large volumes were illegally sourced before being moved through Singapore. In previous studies we found thousands of parrots and cockatoos exported to Singapore from the Solomon Islands that were falsely declared as captive bred when in fact they were wild caught.

Is this still the case? Do illegal birds slip into the legal trade?

There were large discrepancies between what was imported and what was reexported—close to 86,000 birds. It’s highly unlikely that this many birds remained in the country.

One of the greatest problems here is the method of reporting. We strongly recommend Singapore report the actual trade that took place—that is, the quantity of specimens that entered or left the country and not simply the number of permits issued. This would provide a much clearer and more accurate understanding of the trade.

Singapore’s authorities should also exercise greater caution in ascertaining that specimens are imported and reexported in accordance with the provisions of CITES. This includes ensuring that numbers are within permitted quotas, the legitimacy of individuals declared as captive bred, and the origin and legality of nonnative stock.

It’s very likely that many of the birds traded through Singapore have been illegally sourced in their range countries. Of great concern is the number of African gray parrots involved—41,700 were recorded during this period.

Why are African grey parrots such a concern?

African grey parrots are very popular pet birds. As a result of this demand, populations in the wild have suffered greatly over recent years and have been wiped out from parts of their range.

A number of African countries, led by Gabon, are supporting the uplisting of the African grey parrot from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I, the strictest category, later this year when the CITES member governments meet in South Africa.

If actions aren’t taken soon, this species could be lost entirely from many parts of its native range.

What do you recommend for Singapore or other trade hubs?

Better regulation of the import and reexport of birds is essential. In addition to revision of CITES reporting methods, authorities in Singapore or any major trade hub should exercise far more care in ensuring that the species imported and/or reexported have been legally sourced.

Birds, and many other animals in international trade, are often harvested illegally in their countries of origin or falsely declared as being captive bred when in fact they’re wild caught. They’re then laundered into the international wildlife trade, often “legalized" along the way.

Traders know the loopholes well and run circles around enforcement agencies and CITES authorities. These loopholes undermine CITES and facilitate unprecedented levels of illegal trade, leading to the decline of a multitude of species in the wild.

Laurel Neme is a freelance writer and author of Animal Investigators: How the World’s First Wildlife Forensics Lab Is Solving Crimes and Saving Endangered Species and Orangutan Houdini. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook.