Operation Jaguar: Poaching and Human-Wildlife Conflict

From JeffCorwinConnect Citizen Blog:

By Laurel Neme

April 8, 2011

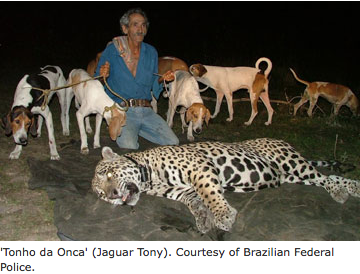

Twenty years ago Brazil’s most notorious jaguar hunter, Teodoro Antonio Melo Neto, also known as “Tonho da onça” or “Jaguar Tony,” swore off poaching after logging 600 kills.

The foe-turned-jaguar-ally began helping conservation agencies track the elusive cats for their monitoring and research and his dramatic change of heart even became the subject of a children’s book, titled Tonho da Onça, which related a conservation message. More recently, however, “Jaguar Tony,” now 71 years old, revealed his true spots when federal agents busted him and seven others for illegal jaguar hunting.

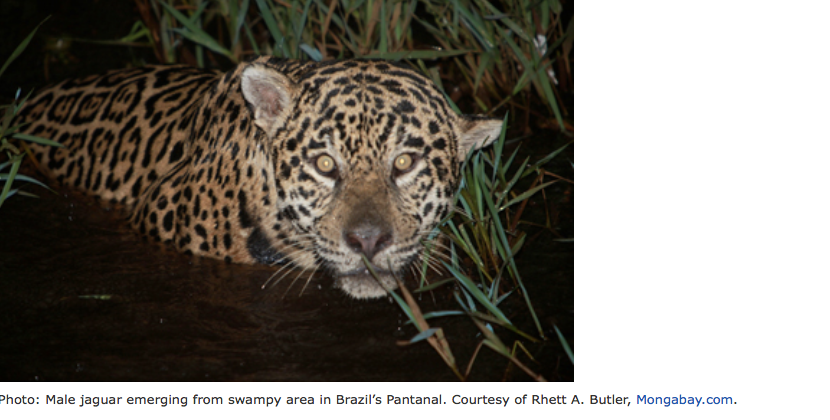

In late 2009, Brazilian federal authorities launched a nine-month investigation, code-named Operation Jaguar, after receiving reports of radio-collared jaguars that had “gone silent” and also of jaguar carcasses on farms in Brazil’s Pantanal, the world’s largest wetland - about the size of Illinois - and prime habitat for the large cats.

The sting culminated in raids across three Brazilian states, one of which was the early morning raid on July 20, 2010 on a Pantanal farm where agents found Jaguar Tony and the others preparing for one more kill. While Jaguar Tony fled, and is believed to be hiding on a Pantanal farm, police did arrest the gang’s ringleader and organizer of the illegal safaris, Elisha Sicoli, a dentist and university professor, Jaguar Tony’s son, who acted as a guide with his father, and their five foreign clients.

The poaching gang targeted jaguars in Brazil’s Pantanal, where it capitalized on tension between ranchers and the large cats. Ninety-five percent of land in the Pantanal is privately owned, with about 2,500 ranches and up to 8 million cattle residing there. At the same time, jaguar habitat is shrinking.

While nobody knows how many wild jaguars remain, worldwide population estimates range from 8,000 to 50,000, and the Pantanal is home to a significant proportion of that, perhaps between 4,000 to 10,000 jaguars. Those realities put livestock and jaguars in constant contact-and conflict. Jaguars feast on the easy prey while ranchers, frustrated by the loss of their livestock, kill the predators or ask or let others do it for them.

Under Brazil’s environmental crimes law killing jaguars is a crime. While in theory the law permits protection of herds from problem predators, the national environment agency, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), virtually never-if ever-has authorized it. Typically, it would capture the problem feline and release it elsewhere.

In essence, Jaguar Tony and his gang provided a dual service: removing a deadly threat to ranchers’ livelihoods and also providing sport for big game hunters. While tourists paid for the privilege, at a price of $1,500 for a five- to seven-day adventure, the ranchers did not. Rather, they provided payment “in kind” by allowing the illicit hunts on their land and also supplying tracking dogs.

The impact of this single gang on jaguar populations is potentially significant. According to the Brazilian Federal Police’s Alessandre Reis, it operated for 20 years and killed up to 50 jaguars annually, or 1,000 animals overall. That means jaguars killed by this one ring may represent as much as one-quarter of the area’s wild jaguar population and up to 12 percent of the world’s.

Whatever the number, Operation Jaguar and stopping this gang will go a long way toward helping the species. At the same time, it underscores the need to address the friction between these predators and ranchers so that law enforcement efforts can have lasting impacts.